Short Story Review || What I Saw of Shiloh (1881)

"The tale told by a soldier who made it through a series of horrors for the honour and principle freedoms of his country."

: 🌕 : SPOILER ALERT : 🌕 :

Uncanny is the flower language that settles over the ravages of war. Bierce’s dedication to evoking dread & hope in the language he used while penning scenes of terror over American soil reveals the man to be in possession of a skill seldom seen. When beginning, the story leaves a reader with a calm enthusiasm for what will be held behind every punctuation & slight hum in the pallet of the author; one is in the company of greatness.

“This is a simple story of a battle; such a tale as may be told by a soldier who is no writer to a reader who is no soldier.”

Yet Bierce does not write for the modern reader. With language that far supersedes modern abilities, the reader of today, one who can hardly fulfill a page’s worth of letters, might lack the gumption required to absorb the material at hand. I found myself curiously in the middle ground, looking over my shoulder at a group I loath to join myself while simultaneously pondering the detail of battlegrounds & slit throats that left me apathetic.

‣‣‣

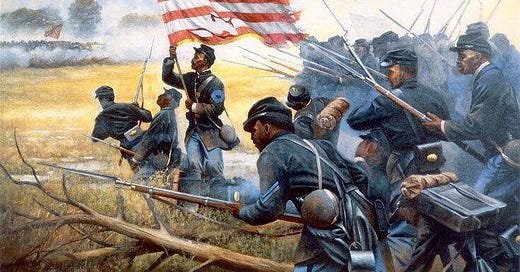

In essence, this is a story about the arrival of Union Soldiers to Shiloh. Bierce recounts the battles that the Union & Confederate Soldiers fought, & their gruelling desire to no longer engage in bloodshed as they witnessed the ease with which death claims all. The characters in this story appear as shadows, their presence seems to indicate that the victor in the American Civil War was the invisible demise that led all to perish, if not physically, psychologically, returning to society burdened by the brutality they inflicted on their neighbours.

‣‣‣

Early on, I found myself struggling to stay focused. The world of today resembles the darkened valour that Bierce describes in the soldier’s quest. One is left with an important question to answer: Who decides whether it is honourable to engage in war?

Upon exploring the riverways, the wielding knives, the lacerated soft skin, the bruised eye sockets, & blazed grass, a reader may feel the need to seek clarity in material that is not so linguistically brutal in its presentation.

Bierce’s story is long. At times, I wandered along with the character as he rambled about a woman who held weapons in the event she should need to use them & wondered about the world where the narrator wandered in memories. On occasion, my mind drifted back to the surrealism presented alongside these flashes of cruelty. It is difficult to hold stable footing when bombs leave one senselessly numb to the world around them. I persevered in my reading.

‣‣‣

I should not wish my rambling to appear trite. I highlight my experience with the material to draw attention to the story’s flow. The introduction felt like a soothing float down the river, while the narrator’s description of wandering through blood-soaked fields, past decaying bodies, & men desperate for freedom, pushed me to the back of the ranks. I remain curious as to why.

Certainly, the body of the text is where the weight of its impact lies. The narrator takes special care to reflect on the consequences of hope that might be found in the assumed honour one holds when going to fight for one’s prerogative, values, & truths.

In reality, what each soldier found was devilish proximity to their demise. This reminded me of the final chapters in Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” (1873). In an attempt to spare the reader from having the book spoiled, I will keep this brief.

Tolstoy presents his readers with the conundrum of war & the sentiment of nationalism that accompanies citizens when setting out to battle. This section, as with Bierce’s story, may be interpreted in different ways depending on the reader. The questions remain the same, regardless of the political landscape. However, their truths may impact readers to varying degrees as the States shift their allegiances. Therefore, one should ponder the philosophical question of the ages: What is the benefit of War?

This review will not seek to respond to that question. What Tolstoy & Bierce allow their readers to ponder is the sentiment intertwined with war. A State decides to engage or refrain from conflict & thus, its citizens are either named as sacrifices or allowed to live unbothered.

What is a person meant to feel with regard to this reality? While Bierce’s narrator wanders along the unmarked graves, translating what he sees, hears, & feels, the reader is meant to be patient. Between the two, the simplicity of the tale overwhelms the senses.

‣‣‣

History, as a thing of the past, lurking to meddle in the present, reveals itself unceremoniously. The narrator could be any man who has ever been called to defend his country, any man who has followed instructions to defeat the enemy—the strange man. What is uniquely devastating is the circumstances. Neither man held by death nor propped by life’s breath are total strangers to one another. Bierce’s sentimentality with regard to the flamboyant intimacy of humanity is felt powerfully in what he writes.

‣‣‣

The narrator’s experiences remain relevant for all readers, though not all will wander the caverns of open landscape, forests, fires, & rivers, beside him as he stagnates over the grooves where his countrymen fell to their deaths. I’m not sure whether I can fault any reader for not wishing to walk through a land where no man should wander.

As I found the cruel pacing of the story a dull reminder of the troubles that befall those around me, those strangers I cannot know, the story gripped my pondering mind, striking me with the pendulum as it pivots.

‣‣‣

Ultimately, though this review has not said much of anything at all, I encourage readers to make their way to the literary talents that Bierce has left us with. This was not a story that was a favourite of mine. However, the talent with which Bierce formats his tales & the spectacular movement of the bow as it weaves the reader into the sentences, makes this story one worth reading.

Indeed, Bierce’s talent renders all sorrowful truths, sour & sweet, like a childhood candy, one that the reader will knowingly remember with fondness. The subject matter, one rebounded on throughout the ages—although the red flower dost remind us never to forget—heaves the burden of humanity’s follies through the brutally sanguine vernacular back into the heart that remains beating.

Readers will find within the diligence of memory & first-hand experience, the brutalist’s art foreboding a promise of languid misery, & yet, this too ends with a firepit for warmth & harmony in song.

Perhaps Bierce’s narrator recognizes the world around him as one that he once knew, though its changes flummox him with curiosity & unease. Perhaps the narrator would find in our modern world the very markers of departure from valour that one believes to be true when marching toe-to-toe into the home of those who are different, seeking to make it something shiny & new.

If you would like to read this story, please visit this link — « What I Saw of Shiloh » by Ambrose Bierce

C. 💌